Meditation Exercises

These tips are meant chiefly for relative beginners to meditation, but I hope everyone can find them useful.

Sit still, don’t move, and just focus on your breath for a few minutes.

It’s the very simplest of notions and most people find it very difficult. Perhaps there’s too much noise, or you can’t get comfortable, or the mental chatter of an active mind distracts you from the breath. There might be pain, or the sense that you should be doing something. Skepticism could creep in, a doubt that sitting here in an apparently unproductive silence could in any way make your life better. You might get hungry, or tired. Or horny.

It’s OK. The first time you played chess, or sat down to pick out a melody at the piano, or cooked scrambled eggs, your performance was probably not world-class, neither would one expect it to have been. But the tenth time, or the hundredth (or, according to research, the ten thousandth) you produced a sixteen-move checkmate, or a perfect transcription of the theme from Ghostbusters, or a plate filled with a steaming hot, tasty breakfast. ‘Practice Makes Perfect’ was drilled in to all of us from

our infant times, but we’re loathe to accept this unwelcome truism. We seek shortcuts to satisfaction, unwilling to go through the tedious repetition involved in actually getting good at something.

But think of every skill you’ve acquired, everything you’re truly good at; it took endless practice and the devotion of time, didn’t it? How many hours did it take? How many times were you humiliated at chess before you got that elusive win? How many times were your scrambled eggs burned or tasteless or rubbery before you dazzled them all with something not only edible, but excellent?

Meditation is exactly the same. It is a practice and it takes practice. It will be hard, it will hurt, and you will want to quit. But if you’re anything like me, you’ll find dividends as soon as you begin which will persuade you that those long stretches of silence and those sore knees are a worthy investment. I’d like to set out some simple exercises which should help organize your sittings to make them more useful, less painful and perhaps even enjoyable.

A very quick caveat: I am not an enlightened being, no two paths to Nirvana are the same, and your knees aren’t my knees. You take my point. [Your mileage may vary.]

Consistency

I know that you can answer this question: Where in your day could you find ten quiet minutes? I feel so certain about this that I’m going to leapfrog the whole issue of not having time to meditate. It’s an excuse everyone uses and it’s the easiest problem to fix. I use it and it feels lame every time. Because I do have time, and so do you. Yes, of course you do; we’re only talking about ten minutes here.

First and foremost, our job as meditators is to sit. It’s the one requirement of this kind of practice. Once you’re sitting, good things can happen. It might sound rudimentary – it truly is – but taking the step of sitting yourself down to meditate will make all the other good things happen.

Deciding to sit doesn’t mean sacrificing a hobby or precious time spent with loved ones; it just means shaving ten minutes off the trivial things you do every day. A friend of mine decided to Tivo pretty well all of the TV he wanted to watch, and calculated he ‘created’ twenty-eight minutes a day by not having to sit through commercials. What do you do, during those commercials? Check your phone, get something from the fridge, maybe deal with a quick household chore. Those are all fine, but I assure you

that sitting is better. Mindless ad-watching is not the only example of time you could easily regain, but for most people, I’ll guess it’s the easiest.

I’ll say it one more time: All You Have To Do Is Sit. If it’s every day, that’s wonderful. If it’s three times a week, that’s wonderful. If it’s twice a month, you know what, that’s wonderful too. The only amount of meditation that isn’t wonderful is none.

Location, Location…

For many people, time isn’t the issue, but where can be the bigger problem. Your kids are running around, or you have a needy pet, or there’s the hum of the fridge, the drone of the AC, the TV baseball commentary coming through the wall. Some meditators insert earplugs, or wear those snazzy noise-canceling headphones, both of which are absolutely fine. And you don’t necessarily need perfect silence. Remember that a big part of meditating is learning to just sit there and accept the unfolding of reality going on around you. On a given day, reality could unfold into a five-alarm fire across town, or the subtly crazy-making sounds of contracting water pipes, or the couple upstairs having selfishly unabashed, room-shaking sex. But that simply doesn’t matter. Be with it. It is, warts and all, what is. That’s the whole point.

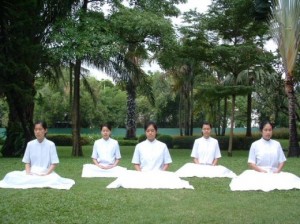

Assume the Position

It won’t always be perfect, but you can indeed grab ten minutes in reasonable peace without interruptions. Then, reward yourself with a big smile and get down to it. Sit on something comfortable so that your hips are slightly higher than your knees. A pile of cushions is great, or piled blankets; almost anything works. Cross your legs. Don’t over-think this part; just find a position which is basically comfortable, and stay there. Straighten your back so that it’s like a tall stack of coins extending from the base of your skull to your tail bone. Then let your weight simply hang from this stack. Try not to move. The only movement should be your breathing, in and out, slowly and relatively deeply.

The Complaints Department

Meditation gives us practice in the simple acknowledgement and acceptance of reality. One of the first things to accept is the way your body feels at a given moment. If we paid close attention we would probably find that we are constantly and minutely adjusting our posture in some way, in response to an itch or a tweak of discomfort. Everyone does it, most of the time without noticing. You’re moving your hair around, or scratching something. You’re shifting your weight, crossing your legs or fidgeting. You’re hot, or cold or you can feel a draught; there are a thousand little voices of complaint.

How about we shut down the complaints department for a while? You can never be completely comfortable; it’s a fool’s errand. Besides, most aches and itches simply go away on their own. Indulging them can only distract from the mindful appreciation of the breath.

So, I invite you to close your eyes, place your hands on your thighs, or curled lightly in your lap, dispassionately observe these myriad sensations and just sit there.

A Moving Stillness

It’s amazing how much you’ll find you’re doing while you’re doing nothing. With the breath as your single focal point, begin to sense the change in the shape of your body as you breathe in and out. Feel how your rib cage expands and relaxes; hear the steady, familiar sounds of inhaling and exhaling. With your mouth closed, focus very intently on your nose and try to feel every molecule of air passing through, in both directions. Inhabit every sensation associated with your breathing.

There is a calmness. Your shoulders might relax, coming forward; return to the upright position, with your spine as that stack of coins. Your head might tilt forward; bring it back into alignment. Do so with a tender and sympathetic affirmation, and never the strictness of an enforcer; you’re here to practice paying attention, but also to practice self-compassion. The upright posture is used by meditators to eliminate sources of distraction and to bring a gentle rigor to the practice. This way, it is differentiated

very clearly from simply sitting on your couch; this is practice, in which you are steadily acquiring a skill.

You might also find that those ten minutes of good posture begin to teach you to sit up straight, just like your teachers told you to in elementary school. Uprightness is linked with attentiveness. I play with an orchestra, and many of its members sit on the edge of their seat with their backs ramrod straight, and I tell you, the focus they bring to their work is unbelievable.

Keeping a Rhythm

Every musical fiber we possess reminds us that humans love to operate in four-square rhythms. We’re bipedal and symmetrical beings; our fingers and toes total a multiple of four; sixty seconds or minutes divide neatly by four, as does twenty-four hours. So, try counting your breaths in groups of four. If your hands are on your thighs, nominate one hand to count the groups of four, and the other hand to count the ‘groups of groups’. Begin with your fingers slightly splayed, with the little finger representing the first breath of each group. As you complete each breath, slightly shift your fourth finger to touch your

pinkie, then your third to touch your ring finger, and finally your index finger to join the other three. Splay them again, and repeat.

As you chalk up quartets of breaths, use your other hand to track your progress, with your pinkie representing the first group of four, your ring finger the second, and so on. This gives you sets of 4 x 4 = 16 breaths, which will take a little under two minutes.

Soon, you’ll become confident in counting to four (!) and you might shift the system; count groups of four with each finger, so a hand accommodates sixteen breaths, and the other hand would track groups of sixteen, so sixty-four breaths, which might take seven or eight minutes. For a beginner, that is a great session of sitting.

You don’t have to count in fours; it could be fives, using your thumbs as well. You could also count with your hands folded lightly in your lap, raising a finger slightly to represent each breath, or group. The point of counting is to provide structure and direction in an otherwise featureless terrain. Experienced meditators do without it, content to focus in a long, continuous stream with the breath as its only guide.

Dealing with Distraction

Sit still for 90 seconds, with a pen and paper to hand. Throughout this apparent stillness, quickly jot down any kind of thought which crops up. The most common ones are our responsibilities, the tasks of the day which remain undone, and the conversations we recently had. You might be expecting a text or an email. An image might appear, of a friend or an enemy, or the gorgeous person you slept with last weekend, or the beach you’ve picked out for your next vacation. There will be a dozen thoughts which come along in that 90 seconds, and none of them will be about your breathing.

Why does this happen?

We all have busy minds which are working quickly on many tasks at once, and as soon as we appear to be doing nothing, the mental ‘chatter’ begins, just to fill that space with something. Some people never work without background noise; I know a composer who can’t write unless he has both the radio and TV on, which might sound nuts, but that’s his habit. Indeed, I’d say we’re all a little habituated to expect frequent inputs, frequent change in our environment. Without it, we become antsy and dissatisfied.

Let me give you an example. I was on a meditation retreat, and after one of the sessions I noted down something of the ‘monologue’ which had permeated my sitting session. It hadn’t been a bad sit, but the ‘chatter’ had been near-continuous. Here’s roughly how it went:

OK, get it together, Graham. Let’s breathe. Here we go. In… Out. In… Out. Nice. In… Out.

Good concentration, keep it up. In… Out. In… Out.

Hang on, can we move this left knee a bit? OK… got it. Try again. In… Out. In… Out. In…

Wait. In… Out. Wait a second. In… Did I forget to go to the bathroom during the last

break? I did? Oh, for God’s sake. Never mind. Nothing I can do about it now.

Back to work. In… Out. In… Out. Oh, nice. In… Out. In… Out. Yeah, I’m totally getting

the hang of this now. In… Out. Meditation superstar, that’s me. In… Out. I could do

this all day. In… Out. In… Out. You know, I’m pretty hungry. In… Out. Why? In… Out.

Because breakfast was absolutely tiny, that’s why. In… Out. How long until lunch? I could

demolish a burger right now. In… Out. In… Crispy French fries, mustard… In… Out. Bacon

and jalapenos on the burger. Oh, yeah. Gonna just destroy one when I get home.

In… Out. In… Out. Good, settle down, that’s better. In… Out. In… Out. Hey, how many

breaths is that? In… Out. Don’t care. Start counting again. Let’s go. In… Out. In… Out.

This knee still isn’t right. In… Out. In… Out. Maybe red onions on the burger, too. In…

Out. In… Out.

Hey, what time do you guess it is?

Admittedly, I was exhausted and starving, but this experience is emblematic of the ‘chatter’. You can turn it off by simply letting it happen and refusing to hang on to each thought as it occurs. There is a lovely metaphor for this: imagine each thought as a cloud; have you ever known a cloud to stop in mid-sky? Of course not, they just keep on going. Let your thoughts do the same thing, just float on by, without reaching up to take hold of them. A friend put it beautifully: “there is no danger involved in

derailing the train of thought”.

A Practice For Life

So, find your ten minutes in a peaceful spot and just sit there. Let go of the thoughts which arise. Suspend the work of the complaints department. Breathe as though it’s your job, your only task for these ten minutes. Then, stand up and return to your life. I’m prepared to bet that, after a few tries, you’ll find a comfortable position, there will be longer and longer stretches between each moment of distraction, and your view of yourself and the world will slowly but certainly begin to improve. You

might notice a little more patience when waiting for things, and that you smile more readily. People often find it easier to avoid ‘sweating the small stuff’ and simply accept the reality unfolding around them. You might forgive more easily, raise your voice a little less, sleep better, feel as though you have more energy. You may even come to look forward to that strangely silent ten minutes (or fifteen, or twenty, or thirty) when all you do is breathe.

Try it before you go to sleep tonight, and try it often, because every second spent meditating is a priceless reward.

Yours in the Dharma,

Dr. Graham Dixon